Article: 1950s – Disaster punctuates exodus

BY DAVID FALCHEK

Published April 23, 2016

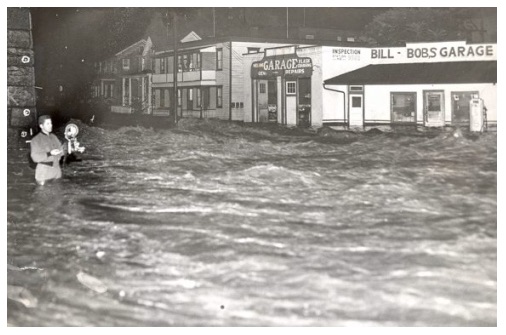

TIMES-TRIBUNE FILE – Scranton Times photographer Phil Butler braves swirling floodwaters at River Street and South Washington Avenue in area where about 35 people were rescued by a Marine Reserve amphibious craft on Aug. 19, 1965. Hurricane Diane wiped out the South Side Flats. [Times-Tribune Archives August 19, 1955]

The 1950s in Scranton weren’t exactly “Happy Days” like those of the post-World War II era depicted on TV.

Family ties remained strong, though frayed by a stagnant economy. A major disaster, Hurricane Diane, hit in the middle of the decade, wiping out an entire Scranton neighborhood.

While the economy may have been lackluster, communities were strong, said Richard Leonori, a child at that time and now an architect and past chairman of the Pennsylvania Historic Preservation Board.

“Ozzie and Harriet” were alive and well in Scranton, he said, even if not as polished as the TV ideal. Children wore hand-me-down clothes and families relied on gardens for food or picked coal for fuel. Scranton’s version of Harriet may have worked out of the home, in a garment factory or at cigar-rolling operations that moved into the area as coal mining continued to decline, dying ultimately with the Knox Mine Disaster on Jan. 22, 1959.

Scranton’s economy failed to keep pace with growing families, making the 1950s the decade when working-age people began to leave the area for jobs, when the families of Hillary Rodham and Joe Biden moved, part of a two-decades-long exodus.

Young Mr. Leonori watched some of his relatives leave for New Jersey and elsewhere. But they remained moored to the Electric City, returning on holidays, filling streets with cars bearing out-of-state plates.

“Families split up in the ’50s,” he said. “Scranton would remain the homestead, but the city lost a good part of that generation.”

The Scranton Chamber of Commerce scrambled into action, its Scranton Plan raising $5 million in the decade to develop industrial sites and shell buildings to lure manufacturers and other business, a bulwark against further economic decline. Borne of urgent necessity, those innovations made the organization a national pioneer.

Churches, synagogues and ethnic organizations were centers of social life, Mr. Leonori said. But the ethnic silos that defined Scranton almost since its inception became porous. The integration provided by schools and mobility afforded by the automobile led to young people of different ethnicities meeting, interacting and marrying, even if parents grumbled.

Hurricane Diane in 1955 wiped out the South Side Flats, a vibrant, predominantly Polish and Jewish neighborhood with homes and a business district. All were washed down the river or ravaged. The disaster led to Scranton’s first modern flood-control project.

Scranton’s namesake asset ended. Scranton Transit Co. went bankrupt and closed in the mid-1950s; the electric streetcars made their final run as individual transportation became the rule of the day. The Scranton–Wilkes-Barre Laurel Line stopped running.

Asphalt displaced rails. The Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike was in the works. The interstate highway system was being designed and many wondered about its implications.

What it cost

- Gypsy suntan cream or lotion: 98 cents (Rexall Drugs)

- Summer mothproof garment storage: $2.95 per box (Cleanrite Cleaners)

- Nemo shocking girdle and panty: $4.95 (Scranton Dry Goods)

- Automobile muffler: $8.79 (The Globe Drive-in Auto Center)

- Chromespun bed set: $9.98 (Bargainland)

- Chrome kitchen table and chairs: $35 (B.J. Smith Furniture Factory)

- Frigidaire refrigerator: $239 with trade-in (Kurlancheek’s)

- Paragon 3-bedroom, pre-cut home: $3,594 (B.E. Snyder)

Notable headlines

Aug. 19, 1955 – “Flood Death Hits Five; Damage Put at Millions, Thousands Homeless”

Jan. 22, 1959 – “Mine Flood Traps 30 Men; 3 Drown as River Pours into Port Griffith”